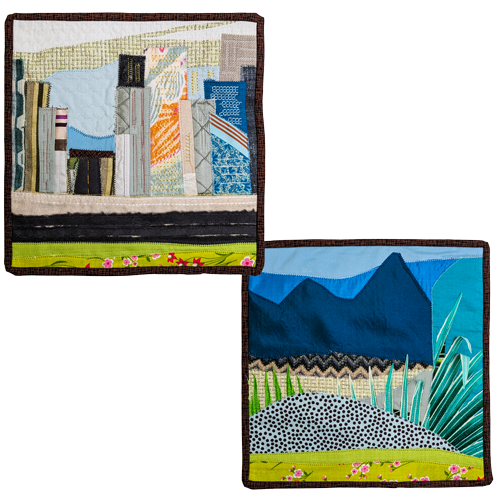

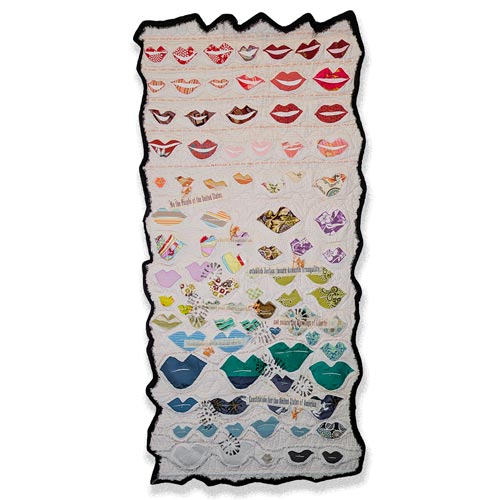

Vintage.

Reclaimed.

Repurposed.

Upcycled.

Imagine... a new life for old things.

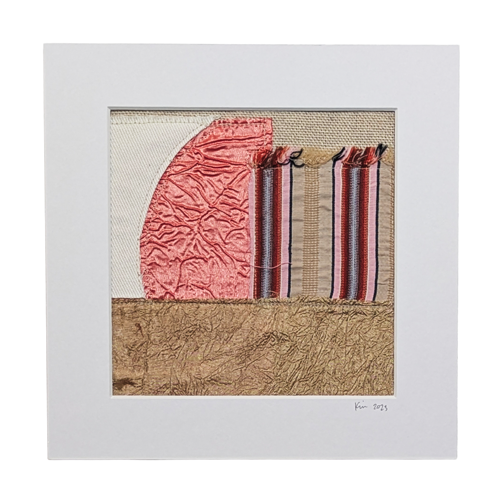

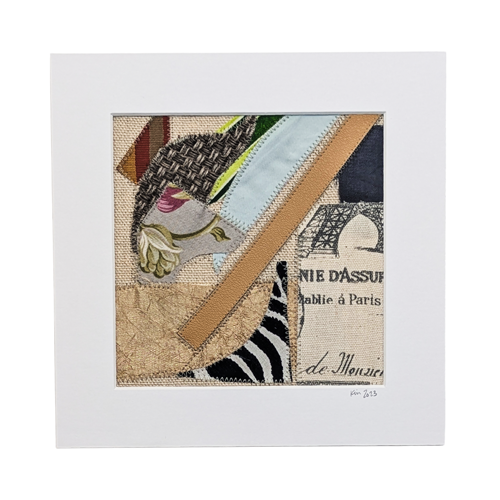

New Release

Woman, Untitled (2026)

Woman, Untitled (2026) is created in the "art of the carry-over."

It argues that our past projects, our discarded fragments, and our "leftovers" are not trash, but the essential building blocks of our next great stride.

It is a portrait of sustainability—not just of materials, but of spirit.